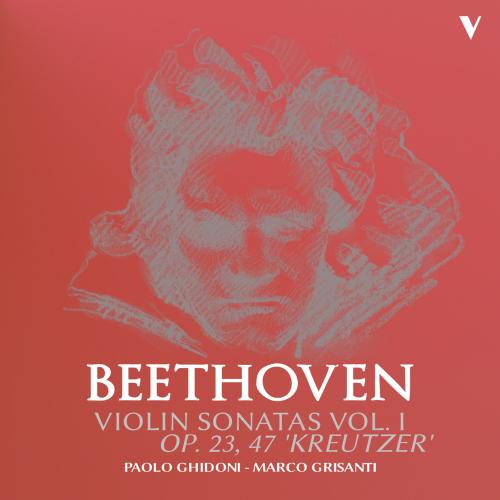

Beethoven: Violin Sonatas Nos. 4 & 9 Paolo Ghidoni & Marco Grisanti

Album info

Album-Release:

2019

HRA-Release:

24.05.2019

Label: OnClassical

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Chamber Music

Artist: Paolo Ghidoni & Marco Grisanti

Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

Album including Album cover

- Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 - 1827): Violin Sonata No. 4 in A Minor, Op. 23:

- 1 Violin Sonata No. 4 in A Minor, Op. 23: I. Presto 07:33

- 2 Violin Sonata No. 4 in A Minor, Op. 23: II. Andante scherzoso, più allegretto 07:54

- 3 Violin Sonata No. 4 in A Minor, Op. 23: III. Allegro molto 05:36

- Violin Sonata No. 9 in A Major, Op. 47 "Kreutzer":

- 4 Violin Sonata No. 9 in A Major, Op. 47 "Kreutzer": I. Adagio sostenuto - Presto 11:32

- 5 Violin Sonata No. 9 in A Major, Op. 47 "Kreutzer": II. Andante con variazioni 16:19

- 6 Violin Sonata No. 9 in A Major, Op. 47 "Kreutzer": III. Presto 07:03

Info for Beethoven: Violin Sonatas Nos. 4 & 9

Beethoven opened the new century with the publication of his first symphony, but also with that of other important works, such as four piano sonatas (Opp. 26, 27, and 28) and two sonatas for piano and violin – in A Minor, Op. 23, and F Major, Op. 24. Originally, the two sonatas were published in 1801 as a set, under the opus number 23. But something as trivial as their having been mistakenly printed on different-size paper in their second reprint a year later compelled the publisher (and Beethoven) to present them as two distinct works, each with its own opus number – probably to save both face and money. Unlike its companion in F major, the Sonata Op. 23 is a rather stark work, remaining in the darkness of minor keys, and often in a contained, two-voice writing in the piano part. Success was granted to Op. 23, however, after a rather negative response to Beethoven’s three earlier works in the genre, published in 1798 as Op. 12.

This achievement encouraged the composer to continue in the genre, with the publication of the Three Sonatas, Op. 30 a year later. Probably written during his sojourn in Heiligenstadt, Beethoven published the works in 1803 and dedicated them to the Tsar Alexander I of Russia. Op. 30 departs from the more traditional writing found in Opp. 12, 23, and 24: both violin and piano parts reach new levels of complexity, with expanded structures, florid virtuosity, and more sophisticated interactions between the two instruments. The final movement of the first of the three sonatas was considered too challenging, and was substituted by a simpler set of variations. During the time the Sonatas Op. 30 were being published, Beethoven began to work on a new sonata for piano and violin. Of ambitious proportions, both in length and difficulty, the sonata is considered the pinnacle of Beethoven’s contribution to the genre. It was published in 1805 as Op. 47. The last movement was a reworked version of the abovementioned discarded rondo from the Sonata in A Major, Op. 30, No. 1; and the opening measures of the first movement, in the key of A major, spiritually seem to connect the final measures of the Sonata, Op. 30, No. 1 to the Presto of the first movement in Op. 47. A peculiar story involves the premiere of the work, given by Beethoven himself and the English violinist George Bridgewater at Vienna’s Augarten Theater, at the early (and uncommon) hour of 8:00 AM on May 24, 1803. According to legend, Bridgewater arrived shortly before the performance was scheduled and performed the work at sight. At a gathering following the performance, the violinist allegedly insulted a woman whom Beethoven admired. The composer left in a rage, and crossed off the dedication of the sonata to Bridgewater. Later, he dedicated the work to Rodolphe Kreutzer, who was considered one of the finest violinists of the early 19th century. Kreutzer, however, never played the sonata, and reportedly disliked it. Violinist Paolo Ghidoni and pianist Marco Grisanti, two consummate Italian artists recognized for their contributions to the chamber-music repertoire, team up in this exciting album, the first of the complete cycle of Beethoven’s sonatas for piano and violin.

The recording was made with two pair of historical microphones Brüel & Kjæer, including 130 volts.

Paolo Ghidoni, violin

Marco Grisanti, piano

Paolo Ghidoni

What can I say about Paolo Ghidon, or “Ghidon” for his friends – a nickname that has always felt a bit too tight for me, maybe because it makes me think of Kremer, who (despite I acknowledge his cunning) is not exactly my musical paragon?

When I was 8, my father put a violin under my chin, but at the beginning I couldn’t care less. Then, when I turned 10, a miracle happened. From that moment on, I started to yield vibrating sounds that would keep me tied to that chunk of wood. I spent hours and hours playing and listening to violin and, largely, orchestra records. Before I reached the age of 18, I graduated as external candidate the Music Academy with a cool 10, without honourable mention or overwhelming agreement, because some teachers didn’t like me at all and forced me to drop out beforehand.

Later, I obtained a run of accolades, culminating with the “Vittorio Gui” international chamber music prize at 19, with Norbert Brainin, first violin of “Quartetto Amadeus”, moved to tears.

Those were years of amazing concerts! With the “Trio Matisse” I played everywhere, and gradually chamber music creeped into me.

And then: a chair at the Conservatory, a solo and duo career with brilliant pianists such as Bruno Canino and Pier Narciso Masi, followed by a period as first violin with the “Virtuosi Italiani”, that gave me the thrill of conducting a string orchestra.

I can’t help mentioning Franco Gulli, at the “Accademia Chigiana”in Siena, the teacher I still remember fondly, a gentleman of bygone times and an extraordinary violinist.

But I can’t neglect my encounter with gifted Ivry Gitlis, and many more…

Hoping not to bore you, that “many more” includes collaborations with distinguished colleagues, beginning from Dino Asciolla, whom I can hardly define as a colleague, since he was–and still is – a myth of my youth.

But the fateful encounter, that I could define a brief and magical journey, was with Sviatoslav Richter. He was in Mantua in 1986 to record for Decca, and my father was a member of the club that had arranged this event.

So one morning I showed up before he arrived on the stage of Teatro Bibiena and I offered him a performance of Bach’s Chaconne. He listened to me intently and gave me some pieces of advice that still represent my “Pillars of Hercules”, for instance that the rhythmic continuity of the opening bars must keep going and also resonate in the following variations.

I remember I had his and David Oistrakh’s “Melodiya” record with me where they played Franck and Brahms’ Symphony No. 3 (I had listened to it a thousand times and it was already damaged), and I told him I loved it. He shook his head and suddenly sat at the piano and started to play the sonata, inviting me, with a “prego” in Italian, to play along. I still can’t understand how I managed to play, but I remember I thanked him with a slight bow and I ran away to cry my eyes out. That was one of the rare occasions I saw my father moved.

In my career I worked with Mario Brunello, Giuliano Carmignola, Danilo Rossi, Ifor James, Franco Maggio Ormezowski, Bruno Canino, Pier Narciso Masi (somehow he evokes Richter’s sound), but the magical encounter of that day in Mantua remains one of the most exciting and prodigious moments in my life.

Now, at 54, I have given about one thousand concerts in trio, as solo and first violin with an orchestra (I think of Pelé and his 1000 goals), still I don’t feel sated with it, not for vainglory, but because I could never live or love without music… I love it too much, and when I listen to Bach, when I play Schumann, I feel alive. Go figure!

This album contains no booklet.