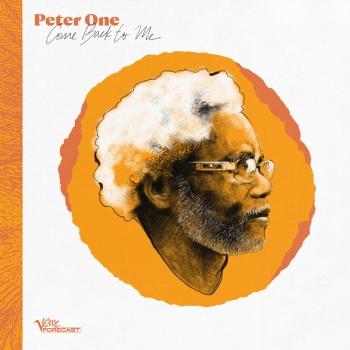

Peter One

Biography Peter One

Peter One

One way we might understand the global Black diaspora is through the notion of arrival—the idea that Black folk in the Americas, in Africa, in Europe, and elsewhere, are and have been, in one way or another, always and already arriving. That is, they have moved or been moved, willingly or otherwise, from one place to another, and in so doing, have adapted, changed, and necessarily reconstituted their own selves as well as the places that they have found themselves, forever. Arrivals are a kind of renewal, signaling birth, beginning, and promise, and—as the scholar Werner Sollors has written—American culture in particular has always emphasized arrivals, arguably more so than points of origin. Literal and metaphoric mobility, perhaps not solely definitive of the American identity, may indeed be close to the essence of global diasporic Blackness as well.

Peter One’s journey as a musician from Cote d’Ivoire to Nashville, Tennessee to today is no different. His life contains its own series of arrivals—again, literal and metaphorical—and each one more surprising than the next. There is a resolutely American bent to the shape of Peter’s story, which reaches beyond even the musical strains and stylings of folk and country that he has mixed together and expertly mastered—and for which he is best known. His story is, in many ways, indistinguishable from the most classic, inspirational immigrant narratives where folks, often against the odds, carve out a place for themselves and their families in a new land, thereby remaking both in the process.

Born Pierre-Evrard Tra—a first and most joyful arrival—Peter One grew up in Bonoua, a small town in southeastern Cote d’Ivoire about thirty miles from Abidjan, the economic center of the

nation. There was only one radio station in Bonoua, though it played all kinds of music–enough to bend Peter’s young ears towards the American country and folk that informs his music to this day. Having first learned guitar at the age of seventeen, Peter developed stylistic affinities for African troubadours like Benin’s G.G. Vickey and the Cameroonian Eboa Lotin, which he began to blend with the chordal and harmonic lushness of some of his American favorites, Simon & Garfunkel and Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young. Hearing Simon & Garfunkel’s “The Boxer” for the first time was transformative for Peter: “That song, it sounded to me like something that I’d heard already, something that I love already, you know? The melodies, the harmonies in the vocals, in the guitar, and the simplicity of the music. Not too many instruments, not too many electronics: it was music the way I want music to be.”

And it would be Peter’s arrival at the University of Abidjan that would eventually lead to him playing stadium-sized crowds in Cote d’Ivoire and across the African continent. Peter’s dormitory mate introduced him to another folk music-lover (with connections at the national TV station) known as Jess Sah Bi, which—after a few broadcast TV performances—led to the recording of their first album, The Garden Needs Its Flowers, in 1985. To differentiate themselves from what was typically seen in Cote d’Ivoire, Peter and Jess consciously imagined their album in the Southwestern American style: with some song titles in English, and the cover design—its colors and Wild-West-inflected fonts—were more reminiscent of American folk productions of the 1970s and early 1980s, while the music itself infused those expansive, scenic sensibilities at points with Ivorian village songs and 1980s Afro-pop flourishes. They sang in French, English, and Gouro, which broadened their appeal. The album ensured the duo’s arrival as stars to their region of greater West Africa, which saw them tour not only the cities of Abidjan and Bouaké, but also neighboring countries like Togo, Benin, Liberia, and Burkina Faso. They played for presidents and first ladies, and their song, “African Chant” was used by the BBC to soundtrack Nelson Mandela’s release from prison in 1990.

With every arrival must inevitably come a departure, and in the mid-1990s, Peter One—ultimately self-effacing at heart, and weary of both the spotlight and the uncertain political situation in Côte d’Ivoire—emigrated to the United States to seek below-the-line expertise as a producer of music. But not unlike the well-told tales of immigrants arriving at Ellis Island—updated for air travel, of course—Peter remembers feeling both excitement and trepidation as the plane that brought him to America began its descent into New York City’s Kennedy Airport. “When I first flew into New York, I could see some parts of the city, Brooklyn and Queens, from the airplane, and I had a little feeling of, ‘Where are you going to start from here? And how?’ And as the cab was driving me to my hotel, I was a little disappointed, to tell you the truth! Because in the movies, you see the beautiful streets, the colors—everything’s nice, attractive. But it wasn’t like that then.” Peter had arrived at a transitional time in New York’s history; parts of the city were just beginning to emerge from a difficult period where places like the Bronx, Harlem, and Brooklyn were more associated with notions of “urban crisis” and the images of abandoned or burning buildings, rather than the “streets paved with gold” of early 20th century immigrant lore.

But even despite his first impressions not meeting expectations, Peter had no illusions about how difficult the road to musical success would be in an entirely new nation. “I knew that it was not going to be easy in the U.S. I knew that nobody knew me here. So I was not big headed. I knew that I had to work hard to find my way.” And like many immigrants of the past and even to this day, Peter One originally had no plans to stay in the U.S. permanently: “I came first to learn how the music business works, to buy my own equipment, and go back home and start my own business as a music producer. But when I got here, I realized that it wasn’t going to be that easy—I wasn’t shocked, but I was determined. I was determined.” That was 1995. The political and social situation then wasn’t getting any better in Cote d’Ivoire, so Peter knew he had to pivot and as he says, “make a Plan B.”

Peter’s journey in America took him from New York to Delaware and, finally, to Nashville, where he has settled with his family, all along taking a series of jobs in a field that seemingly had little to do with music producing: nursing. In some ways, Peter’s adopted profession—necessary to provide for his family—brought him both further away and closer to his goal, since it was nursing that brought him to Nashville, a.k.a. Music City. “I never thought about living in Nashville—never—until I got a job here! But when I landed here, I went to Broadway and I could just feel it, and I said, ‘this is a place for music.’ I saw music everywhere—everybody plays music, everybody’s a musician—and I said, ‘Wow, this is the world for me.” But even so, and for someone who had been a mainstay of both radio and Abidjan club playlists in their home country, Peter would toil in relative obscurity in Nashville for years—until 2018.

An enterprising former Fulbright scholar named Brian Shimkovitz who had spent time in West Africa in the early 2000s had started a record label called Awesome Tapes from Africa, and wantedto re-release Our Garden Needs Its Flowers. He reached out to Jess and Peter, and the three of them agreed to do so—and to glowing reviews in Pitchfork and Rolling Stone. Peter’s dream—not ofstardom, but of making a living as a musician—which had threatened to elude him as the dreams of immigrants so often do in America, was once again within reach.

And as anyone who hears the first ebullient, inviting notes of “Cherie Vico” on Peter’s new album will surely tell you, Peter One has once again arrived, and he has brought with him a set of songs that might just transport their listeners to new vistas, new moods, and new modes of experience, because they are the reflection of Peter’s own unpredictable, ever-surprising journey. There is a joyfulness that emanates from so many of the tracks which seems boundless, though even Peter is hard-pressed to account for the source of that joy: “You know, some scientists, or philosophers, or psychologists,” he says jokingly, “they say that as humans we live several lives, and maybe in a previous life I came across this kind of music—I don’t know. But I really love the way that music is expressed through folk music—all kinds of folk music are really touching to me.” Also reflective of that immigrant’s journey—again, a resolutely American tale, in more ways than one (Peter became an American citizen in 2008)—is his desire for the quality of his work, his music, to shine through first, no matter what language in which he may sing. “If people love those songs in African languages even more than the English songs, I’ll be really happy because then I know that the music is making the connection.”

That said, it is the refrain from the contemplative, soulful, “On My Own”—written in English— which succinctly expresses so much of what has made Peter One’s improbable arrival so inspiring: “On my own, I came a long, long way.”