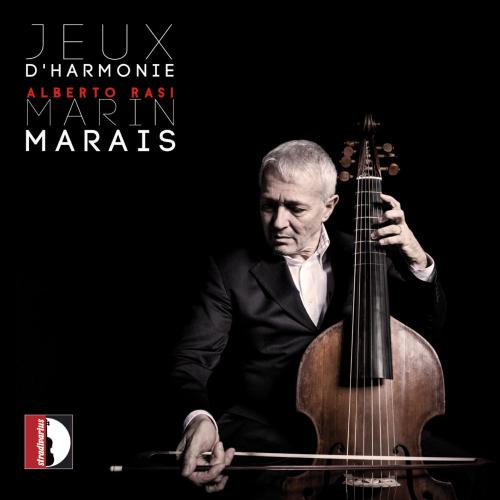

Marais: Jeux d'harmonie Alberto Rasi

Album Info

Album Veröffentlichung:

2017

HRA-Veröffentlichung:

27.01.2017

Label: Stradivarius

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Chamber Music

Interpret: Alberto Rasi

Komponist: Marin Marais

Das Album enthält Albumcover

- Marin Marais (1656-1728):

- 1 Pieces de viole, Book 1: Suite No. 1 in D Minor: No. 1. Prelude 04:20

- 2 Pièces de viole, Book 4: Suite No. 1 in D Minor: No. 4. Caprice 01:45

- 3 Pièces de viole, Book 2: Suite No. 3 in D Major: No. 63. Les Voix humanes 05:53

- 4 Pièces de viole, Book 3, Suite No. 4 in D Major: Pieces de viole, Book 3: Suite No. 4 in D Major: No. 54. Rondeau 04:04

- 5 Pièces de viole, Book 4, Suite d'un goût etranger: No. 80. Arabasque 05:50

- 6 Pièces de viole, Book 4, Suite d'un goût etranger: No. 82. La Reveuse 04:30

- 7 Pièces de viole, Book 3, Suite No. 8 in C Major: No. 109. Caprice 01:07

- 8 Pièces de viole, Book 3, Suite No. 8 in C Major: No. 110. Allemande - No. 111. Double 02:30

- 9 Pièces de viole, Book 4: Suite No.4 in A minor: No. 28. Musette - No. 29. Musette 02:33

- 10 Pièces de viole, Book 5: Suite No. 1 in A Minor: No. 15. Rondeau moitié pincé 03:19

- 11 Pièces de viole, Book 4, Suite d'un goût etranger: No. 55b. Marche tartare 01:56

- 12 Pièces de viole, Book 4, Suite d'un goût etranger: No. 58. La Tartarine - 59. Double 02:20

- 13 Pièces de viole, Book 5: Suite No. 7 in E Minor: No. 107. Le Caprice Bellemont 06:17

- 14 Pièces de viole, Book 3: Suite No. 6 in G Minor: No. 91. Le Moulinet 04:51

- 15 Pièces de viole, Book 2: Suite No. 4 in G Major: No. 82. Chaconne en Rondeau 05:37

- 16 Pièces de viole, Book 2: Suite No. 6 in E Minor: No. 101. Sarabande a l'Español 03:01

- 17 Pièces de viole, Book 5: Suite No. 6 in G Major: No. 87. Le Joue du volent 02:12

Info zu Marais: Jeux d'harmonie

In seventeenth-century France, every aspect of fashionable society was governed by the laws of galanterie, which behind the règles de bienséance et de politesse hid their only purpose: seduction. Music, too, was part of this, with all the seductive power that it possesses, in the social rituals in the salons, the temples of vivre galant; it, too, adapted so much to the styles of salon conversation, that already Marine Mersenne (Harmonie universelle, 1637) spoke of musical interpretation (in reference to singing) as the Art de l’Orateur Harmonique, which must “know all the nuances, the tempi, the movements and the accents to arouse everything he desires in those who listen”. In effect, also this is the art of seduction, which the human voice is able to practise better than any other instrument.

While singing remains the term of reference for representation in sound of affections, the most important of the instruments is the viola da gamba, able to imitate the voice “in all its modulations and its accents of joy and sadness […] agility, gentleness and strength, vivacity and languidness”. These are more words from Mersenne, who compared the excellence of the players in the bons concerts de Violes to the “grace of a perfect Orator”. Besides its expressive qualities, the viola da gamba possessed the ancient nobility of tradition and innate elegance of gesture that in a setting as attentive to detail and appearance as the salons became an important advantage. The player’s posture and movements, and the ability to behave with the grace of a galant homme, were perceived as an element in social communication. Treatises and Avertissements introducing the collections of viol works identified a close relationship between instrumental technique and the gestures that express it, as if to say that the aesthetics of sound and those of the gesture are a unified whole. In the game of musical seduction, what pleases the ear must please the eye.

Violinists disagreed about how best to express on the instrument the art of the orateur harmonique. For Jean Rousseau, “the viola da gamba is equal to the voice and its aim must be to imitate that unique model of beauty which is the voice and its ornaments”; it is just because the viola is the instrument closest to the voice that in playing it “the melody must preferably dominate over the harmony, as its soul is in the grace of the singing, and this is the only reason it is valued” (Traité de la viole, 1687). In the jeu de melodie, in the pure melodic dimension, the natural vocation of the instrument to “tenderness [tendresse] of sound due to fine bowing which are its soul, and mellow it so beautifully so anyone who listens is enthralled” (Jean Rousseau).

In contrast, Le Sieur De Machy (Pièces de viole en musique, 1685) considered playing pièces d’harmonie (which contained chords) the first and most common way of playing the viola da gamba, «characteristic of all the instruments that are played alone ». Disagreeing with those who maintained that exclusively melodic pieces were preferable to those embellished by harmonies, De Machy stated that “one’s hands can be well placed and one can play fine melodies gracefully, no matter how simple they are; but this is like playing the harpsichord or the organ perfectly with one hand. This, too, may be a pleasant way mode of playing, but we should certainly not say that it meant playing the harpsichord or the organ”. It was not true, continued De Machy, that in the jeu d’harmonie the use of chords prevented the left hand from ensuring adequately the beauty of the sound and of the melody: “It will not be chords that create difficulty for those who know well the craft of composing beautiful melodies with all the ornaments necessary for expressiveness of execution”.

Viol players seemed to have differing opinions between the “natural” of the melodie and the “artifice” of the harmonie. But whatever the jeu, it was still the amorous game of seduction, in which nothing was what it seemed. The attraction of a fine melody certainly lay in its natural singing grace, but no less in the calculated care of the bowing and the dynamics, of the ornamentation which gave the melodic line the indispensable element of elegance and good taste. On the other hand, in the aesthetic rule of the orateur harmonique, everything that delights the senses and moves the affections – from the music itself to the gesture of execution – is “second nature”, no matter how artificial the means leading to the result. Similarly, the violinist tackling the most complex designs of the jeu d’harmonie would tend to make the artifices of virtuosismo appear as natural as possible by using “a certain nonchalance in everything, which hides art and demonstrates that what is done and said is being performed without effort and almost without thinking”, according to the still valid teaching of Baldessar Castiglione (Il libro del cortegiano, 1528).

The formula is that of every bon discours, also musical: “suggested by nature, embellished by art”. In this sense, “well-executed embellishments are for singing what rhetorical devices are for eloquence. With these devices a great orator moves hearts as he pleases, takes them where he wishes, and thus arouses every kind of emotion within them. Embellishment produces the same effects in singing” (Jean-Baptiste Berard, L’Art du chant, 1755). It is evident in this aesthetic perspective what importance is attributed to ornamental apparatuses – from the space given by Marin Marais to the illustration of the various agréments in the prefaces to his five books of Pièces de viole (1686, 1701, 1711, 1717, 1725). This is because “exquisiteness [delicatesse] in playing the viol consists in a certain ornamentation characteristic of the instrument » (1er Livre) and “the most beautiful pieces lose most of their attractiveness, if they are not performed according to the style [goût] which is theirs ».

It was all a question of goût: the key word of gallant aesthetics, referring both to the feeling of the beautiful and the pleasure that it produces (taste), and to the object valued (style). In preparing a printed musical collection, the obligation of the composer was principally directed to reconciling the style – the character of the pieces – within the tastes of the potential users, considering also their different technical abilities, as he did not fail to mention several times in the Avertissements of his books. The composer was very attentive to detail, and made sure that his Pièces de viole contained “short, easily executed pieces » and others which were «dense, with many chords and several varied repetitions [doubles], to satisfy the most advanced players”, diversified in style “so that each one can find what is most pleasing” in a musical corpus which in the end would number more than 550 compositions, grouped into suites, each one with a number of pieces varying from 5 to 21. There had to be dances, the homage to the very essence of French music and fashionable ceremonies, starting from those of the court, of which they were the soul. But it is above all the pièces caracterisées scattered through the five books that show Marais’ mastery in interpreting with great originality the resources of the jeu d’harmonie, in a variety of technical solutions. These are sometimes vey demanding, ever more associated with stylistic or expressive inventions, also these new and sometimes strange. Still more obvious are the peculiarities of writing and character of these pieces in an execution on solo viol without the support of the basso continuo, integrating it if necessary into the harmony. On the other hand, it is evident how the inclination of Marais approached that of De Machy, who included the viola da gamba (low register), with the harpsichord, lute, theorbo and guitar among the instruments “qui font d’harmonie d’eux-mêmes”, without the need for additional parts.

Apart from the dances, the Pièces de viole pay homage to the fashionable world of the salons with pieces like La Guitare (a very fashionable instrument in the France of that time). For this, as for Le Moulinet, Marais gives precise indications for the execution arpeggi, which are essential in these pieces (the term moulinet, whirl, could perhaps refer to the broad gesture of the bow stroke of the arpeggio). Another instrumental evocation is the Muzette II with the “pedal” effect recalling the drone of the French bagpipes (musette). A brilliant distraction, perfectly in tune with the subject, then characterises Le Jeu du Volant, a piece full of virtuoso nimbleness that depicts the movement of the shuttlecock in badminton struck by the players.

While contemplative pieces such as La Rêveuse and Les Voix Humaines show how the jeu d’harmonie can also take on an intense lyrical and sentimental expressiveness, what best characterises the interpretation of this style in Marais is the enthralling ideas of pieces like the Rondeau moitié pincé et moitié coup d’archet, where pizzicato sections alternate with bowed sections (there were those who, like Jean Rousseau, consider pizzicato inappropriate for the viola da gamba), or the elaborate Arabesque for which the composer admits “having broken the customary rules” with some daring leaps in the chords, “since the effect seemed to me to be pleasant and it also facilitated the position of the hand”.

Hubert Le Blanc attested to the fascination a piece like this had continued to exert many years later (Defense de la basse de viole, 1740). For him, L’Arabesque would be enough to demonstrate the great loss of a figure like Marais, in whose music there burns “the living flame of youth, full of vitality and charm”. (Marco Materassi)

Alberto Rasi, Viola da gamba

The Accademia Strumentale Italiana

was founded in Verona in 1981 with the specific purpose of recreating the atmospheres of those ancient and illustriuos academies, where the pleasure of meeting one another gave a special flavour to making music together. Its repertoire encompasses instrumental and vocal music ranging from the Renaissance to the early Baroque, performed according to strict philological canons, but without compromising its ability to comunicate with the present. The Accademia has performed extensively in Italy, Spain, France, Belgium, Switzerland, Austria and Germany and has been invited to several international festivals where it has always met with widespread critical acclaim.

The members of the Accademia are all renowned specialists in ancient music and have worked together with some of the most famous European ensembles, such as Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, Hesperion XXI, la Reverdie, I Sonatori de la Gioiosa Marca, Europa Galante and others.The Accademia Strumentale won the “Midem Classical Award 2007” with the CD “Dolcissimo Sospiro” containing music by Giulio Caccini and others.

Since 1991 Alberto Rasi has been the group’s musical director: the ensemble is currently composed of consort of viols, who are joined by guest artists who are invited to partake in larger projects.

Dieses Album enthält kein Booklet